EXTRACT FOR

THE CADET REGIME

(Charles Ryder)

|

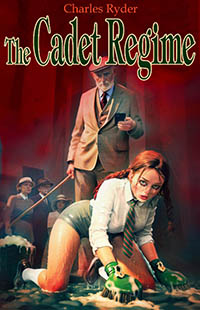

The Cadet Regime CHARLES RYDER Chapter 1

The

morning really began with the anthem. Tinny and hollow, it spilled from the

rusted speaker bolted to the post outside the bakery, as it did every day at

07:00 sharp. Union Jacks rippled above the shop fronts, and across the village

square, people were already out, sipping tea, sweeping thresholds, pretending

not to wait for the daily entertainment. 19 year

old Alice Morton knelt on the tarmac outside the post office, scrubbing at a

tar-stained patch with a harsh-bristled brush and a tin bucket of soapy water.

Her sleeves were rolled up to her elbows. Her arms

were red, raw. Her shirt, stiff,

starched, gleaming white, clung to her shoulders in the damp morning

air. Her tie, striped in the

colours of the local area cadet organisation, sky blue and yellow, was tightly knotted and immaculately aligned,

pulling at the high collar that chafed against her throat every time she bent

forward. She

scrubbed without looking up. She had learned that much. Behind her, a pair of

pensioners chuckled by the bench. "Look at

Lady Morton go," one said. "Told you all she needed was a good brush and a

bucket." "Should've made her clean the old war memorial. Her lot never

respected it." "She'll get to it. They all do, sooner or

later." The Cadet

Service had been introduced six months ago, officially

described as "Reintegration for the Unprepared Youth of Dissident Lineage."

Unofficially, everyone knew exactly what it meant: make the daughters pay. Not in prison nor in court. But in full view so that everyone could see.

She dipped her cloth clumsily into her bucket and it tipped slightly. Water

sloshed over her bare knees. "Missed a

bit there, sweetheart," called a voice from across the road, Shirley Dawes,

from the hairdresser's, smoking a cigarette and grinning wide. Alice's

hands trembled as she righted the bucket. "Don't

shake, now," Shirley continued. "You're not in drama school anymore." More

laughter. A phone camera flicked on with a soft chime. "Smile

for the Grey Channel, darling," someone said. "Might make Clip of the Day if you sniffle a bit

more." Alice

sniffled. But not for the cameras. Her knees hurt. Her fingers were aching. Her

cheeks were burning. The knot of her tie dug into the soft skin of her throat.

This was so far removed from her previous existence

that sometimes it felt like a sort of surreal dream. She scrubbed harder, if

only to show the ever-present cameras that she was trying her hardest. A young

boy passed by with his mother and stared at her. "Why's

the lady washing the road?" he asked. "Because

she used to think she was better than us," the mother replied, with a slight

sneer. "Is she

bad?" asked the boy, innocently. "Not yet.

But she was raised

wrong. And now she's learning." And that,

of course, was the point. The work was only part of the punishment. The real

purpose was display, ritual humiliation, watched and

endorsed by the people whose lives, according to the New Government, had been made harder by the "liberal elite." Alice's mother had

signed petitions. Her father had spoken at rallies. There was even a video of

him calling the Prime Minister a "cartoon autocrat." That clip had resurfaced

during the early purges. Alice had been processed, and

handed a uniform. And now she scrubbed. "Bit slow

today, aren't we?" came another voice. A shop assistant with a clipboard and a

Civic Youth pin. She looked barely sixteen. "Pick up

the pace, Cadet." Alice

nodded. "Yes, ma'am." The girl

laughed. "Say it louder. You've got an audience." Alice

grit her teeth and tried to keep her voice even. "Yes,

ma'am." The

villagers nodded. Some smiled. A few

even clapped. The Cadet Handbook called it service. The Ministry called it character restoration. The broadcast called it a brighter future for all. But here on

the tarmac, with soapy knees and splinters in her hands, Alice knew what it

really was. It was revenge. Revenge for perceived injustices that she and her

family, especially her parents had been found guilty

by the court of public trial and condemned. Just

exactly what she herself was guilty of was never fully

explained. It seemed enough that she's been seen on various student rallies although no one in

authority seemed to care much what she had or hadn't said on those marches. The point was that her parents

had clearly been anti-New Government and therefore by extension so was she. Although in

reality she was being punished, and very

publicly punished, for the sins of her parents and those of her parent' friends.

She knew

from bitter experience that every second of this humiliating exercise that she

was struggling with was not only being watched by an amused, spiteful live

audience but, and as if that wasn't bad enough, it was also being live-streamed

from the drone that hovered disconcertingly close to her capturing both an

image of her and the reaction from all around her. That piece of film and the

stills from it would be watched later by an audience

of millions. People

would pay to watch it on the Grey Channel. A monthly charge to watch her entire

ordeal from start to finish or perhaps just a

highlight reel. They'd pause and

rewind and make their own stills for their own enjoyment and

satisfaction and share them with others. The justification was that "this

proves the system was working." The New Government had promised to bring "the

traitors in our midst" to justice and that's exactly

what they were doing. And that clearly resonated... "Owowowwooow." The

sudden impact of a thin cane, expertly wielded by an experienced hand

unexpectedly bit into the thin material of her skin tight shorts making Alice

squeal in shock. "Stop

your daydreaming, cadet. There's still a lot of road that need scrubbing." Instructed the volunteer

in her prim voice that wouldn't have sounded out of

place at a garden party. "Ohhhh...ow...sorry,

ma'am." Alice

gasped out her apology. She wasn't even sure if she

was meant to apologise for doing nothing other than pause for a second to ease

her aching back but experience had taught her that it was better to be safe than sorry in any

interaction with an official when she was dressed in

her cadet uniform. Instead , to try and alleviate the tedium of her laborious

chore she allowed her mind to drift again, but this time scrubbed more

enthusiastically. Dipping her well-used brush back into the scummy lukewarm water

by her side. Chapter 2

Fenella

Lancaster had once been described, by her family, her

friends, teachers, and anyone who met her, as "lovely." It wasn't a compliment. It was a fact. She smiled at

shopkeepers. She remembered people's birthdays. She said sorry even when it wasn't her fault. At 18, she had been studying drama at a

minor London college, largely sheltered from the

sharper edges of politics. She lived in a nice flat that her mummy and daddy

had bought for her. She bought vegan cookies for her friends. She wore linen

and knitted scarves and didn't post very much online. Her

parents, however, did. Elinor

and David Lancaster had been beloved icons of the theatre world. And then, as

so many of their kind, developed into outspoken thorns in the side of the New

Government. Their final play, "The Silence Between Us," was described by Party media as "an act of artistic

terrorism." Within weeks, they were gone. Publicly arrested so that

everyone watching that evening's news would know that they were enemies of the

State. They were never

tried but presumably they were in some sort of government institution somewhere. Fenella, who

had been at a rehearsal for Twelfth Night when they came for her, didn't even get to collect her things. Now, she

walked in the midday sun with a grabber stick and a grey bin bag, picking

litter along the kerb opposite Alice Morton. Her hair, once long and softly

curled, had been trimmed to regulation length. Her shirt was gleaming white, so stiff it didn't move when she bent. Her tie, yellow and sky-blue striped like Alice's, was tight against her throat, pinching

each time she looked down to collect a crisp packet or a plastic bottle. She was red-faced, flushed from exertion,

humiliation, and tears. Not sobbing. Not breaking. Just... crying, the way a child cries after

falling, quietly, hopelessly, and with no one to comfort her. A boy on a bike

rode past and jeered. "Pick it

up faster, theatre girl!" Two women

sipping at drinks nearby laughed, one raising her phone. "She used

to be on telly, didn't she?" "Yeah,

now look at her, finally earning her keep." Fenella

bent to grab a fast food wrapper, hands shaking. She nodded politely,

automatically. Always polite, always lovely.

She didn't speak anymore, not unless instructed. Her

voice had been mocked too many times, too posh, too performative, and

too sorry. The Ministry said she was "emotionally excessive." Her

Obedience Rating had plateaued at 62%. "Needs

firmer structure," her handler had written."Potential for public resonance

remains high. Recommend more street work." She had

cried when she was first made to pick litter. Now she

cried less, which meant she was "improving." But she still flinched

every time someone called her name-not Fenella, but Cadet Lancaster. She wondered,

sometimes, if her parents were watching. If they were proud? Or ashamed. If

they were even alive? Fenella's eyes

stung at the thought. Not from the wind, not from the sweat, not even from the

dirt. But from the humiliation.

It lived just behind her eyes now. Always ready. Always close. She bent,

knees trembling slightly, as she used the grabber to fish a crumpled, sticky

paper bag from a flowerbed. Her hands ached from clenching the tool. Her shirt was immaculate, but soaked with sweat. Her tie choked her, snug under her throat,

the knot unyielding. She was crying again. Quietly. Like always because as she

was only too aware she was being

watched all the time Behind

her, boots scuffed against pavement. Slow. Deliberate. It was two men, old and

sour-faced with flat caps and grubby old jackets. Watching her with the kind of

smile that didn't belong anywhere near a person's

suffering, but one that thrived

in this new world. "Oi, Red,"

one of them called. "That one there, missed a bit. What's

the matter, never cleaned a gutter in Kensington?" Fenella

stood up at once. Straight-backed.

Hands held behind her, heels together and eyes forward. The Regulation Posture for when engaged by a

member of the general public, no matter what their

age, sex or status. "Good

morning, sir," she said softly, voice wobbling but clear. "I apologise for the

oversight. I'll correct it immediately." "Very

polite," the other man said, stepping closer. "Almost like she actually

believes what she's saying." They both

chuckled. Fenella kept her eyes on the building across the street. She focused

on the cracks in the stone, as if by concentrating she could drown out the

present.. "What's

your name, girl?" "Cadet

Fenella Lancaster, sir." "Lancaster?"

the first man said, feigning surprise. "Any relation to those luvvie traitors

what did the play about how the country's a prison?" "Yes,

sir. They are my parents." She said

it automatically. She wasn't allowed to pretend

otherwise. "Ah," the

second man said. "So you're why my granddaughter can't wear pink hair anymore. Cultural sabotage, was it?" More

laughter. One of them reached out and flicked the knot of her tie, making it

jerk tight against her neck. Fenella flinched, but did not move. He took a

firmer grip on it and yanked it downwards a little. Something that officially

he wasn't supposed to do but he was an old man and who

was going to deny an elderly gent like him something that he evidently

took great pleasure in? "You must

miss the stage," the first one said. "You had the look for it, y'know. All that

long hair. That... posture." But even

as he said it, the tone changed and took on a more threatening mood. "Bet you

were the star of the show, weren't you? Daddy's golden girl? And now you're out

here picking up chip wrappers in front of real people." Another

tug on her striped tie, not so gentle this time. Fenella's lip trembled. She

fought to speak. "It is my

honour to serve the community, sir." "Look at

that," the man said to his friend. "Didn't even crack.

Well-trained." "Go on,

then," the other said. "Say it. Tell us you're

grateful. For being corrected." Her voice

caught in her throat. "Say it,"

he snapped with a more forceful tug that pulled her head forwards "I... I

am grateful," she whispered. "For the opportunity to correct my upbringing.

And... and to earn the forgiveness of the people." "Louder!" "I am

grateful, sir," she said, this time louder. Shaking. Weeping now. "Thank you

for allowing me to learn. I...I will serve better." They

stared at her for a moment longer. Then laughed again. "Good

girl." They

walked away. Fenella remained standing. Shoulders trembling. Hot, bitter tears

trailing down her cheeks. The grabber

slipped in her hands. Her hands

went automatically to her throat to remove and re-tighten her tie back to an

acceptable standard. A disorganised

uniform was a disorganised mind she remembered and would lead inevitably to

some sort of corporal punishment. Once it was knotted to her satisfaction

she bent down slowly and picked the grabber up. The wrapper was still in the

gutter. She placed it gently into the sack. The tears didn't

stop. |